When I met Clive 'Zanda' Alexander

January 23, 2022

Dedicated to the calypso jazz fraternity: Raf Robertson, Tony Voisin, David Marcelin, Michael Meggie Clarke, Russ

Henderson, Scofield Pilgrim, Rupert Clemendor, Andre Tanker, John Buddy Williams, Newman Alexander, Wilfred Woodley and Fitzroy Coleman.

I first met the charismatic Zanda in 1967. I was 14, and positioned as student vice-president of the second-phase QRC Jazz Club. Zanda had returned to Trinidad from his studies in England.

The QRC Jazz Club was founded by Scofield Pilgrim in 1960. He was the Latin teacher there.

QRC was the high school that had produced world-renowned thinkers as Eric Williams, Lloyd Best, VS Naipaul, Geoffrey Holder, Peter Minshall and Rudy “The Pharaoh” Piggott, to name a few. Scofield was a bohemian, intellectual, educator, musician and jazz aficionado.

He was known as the father of calypso jazz. At the beginning of the jazz club, he initiated the term “calypso jazz” after the progenitors of Russ Henderson, Rupert Clemendor, Rudy “Two Left” Smith and others who laid the groundwork and foundation for the expression in the region and in Europe. There was always calypso jazz, expressed from the 1920s by road bands and Carnival procession jam bands. Processional expression was always fused with multi-cross rhythms of the Afrocentric/South American variations from the Caribbean. In the history of North American jazz, it was noted that calypso had a pivotal influence, adding the rhythmic sway and cut-time syncopation to the Dixieland jazz march style and representation.

Scofield and the scholars knew of this, and reconstituted the concept, promoting their revised history for the new independent Caribbean. Most of the historic and anthropologic studies of the day were Eurocentric –and still are. Though the works of Lomax and the like were important and foundational to the ethnomusicology and anthropological sciences, on the ground certain histories were resorted to.

The musicians, big bands and combos played their part in their organisations and styles in the 50s and 60s against the new organised expression of the steel drum, the pan. The calypso phrasing and posturing mixed with the compelling clave, offbeat syncopation (the iron rhythm), progressions and montunos, the calypsonians' gestures and caricatures, created a language inherent in the music of calypso jazz.

There was a sect of musicians which I would call transcendentalists/calypso scientists. They were those whose musical language was ingrained in the calypso jazz expression. These were gifted musicians in various organised bands and collaborations of music arrangers, soloists, instrumentalists, vocalists and calypsonians. There was a sophistication. There was a music before the pan music which the pan musicians and arrangers emulated. This was calypso jazz.

This was the undercurrent of the QRC Jazz Club environment throughout the 60s. The first-phase Jazz Club 1960-65 students were Ray Holman, Monty Williams, Mike Georges, Michael Golding, Kenny Daniel, Wayne Kirton, John Smith, Feroze Ali, Johnny Blake, Trevor George, the Maharaj brothers, the Doyle brothers, Peter Farmer and other music-enthusiastic students.

The club was a formal club, with members, presidents, vice presidents secretaries and treasurers. Not all were musicians. Some were project helpers as stage managers and performers' support.

The mix ensembles consisted of a small steel ensemble and conventional instruments ensemble, and then combinations. I was in the second phase of the Jazz Club. The students were Wayne Bonaparte (president), me, David Boothman (vice president), Bill Henry (secretary), Ruthnath Sahadeo (treasurer); inbetweeners were Bruce Price, David Thompson, Richard and Stephen Seepaul, Hamid Ali, David Thompson, Freddie Arjune, Neil Payne, Garth Brathwaite, Noel Farrell, Michael Benoit, and other supporting students. The activities during the school week and Saturdays were, lectures, repertoire practice and performances.

In the mid-60s Scofield became director of the Caribbean’s Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme, which facilitated Caribbean programmes and cultural exchanges across the region. The jazz club was the mechanism of the exchanges. The club played in high schools – Bishop Anstey, St Francois, St Mary’s College – as well as UWI, Queen's Hall, Naparima Bowl and a few social clubs in Port of Spain.

There were other collaboration with popular musicians, choreographers, and intellectuals. The club became popular for the jazz sessions on Saturdays at the school. There were also exchanges between Shango Yoruba research and Hindu traditions and music.

Visiting musicians were Andre Tanker, Ken Joseph (senior), Felix Roach, Larry Atwell, Wilfred Woodley, Mervyn De Gannes, Braff, Robert Bailey, Michael Boothman, Happy Williams, Michael “Toby” Tobias, Kenny Lohar, Felix Roach, Errol Wise, Ralph Davies, Syl Dopson, Russ Henderson (when in town) and his brother John, along with the alumni Michael Georges, Wayne Kirton, Zanda’s cousin Mojay, brother Carlton Zanda and others.

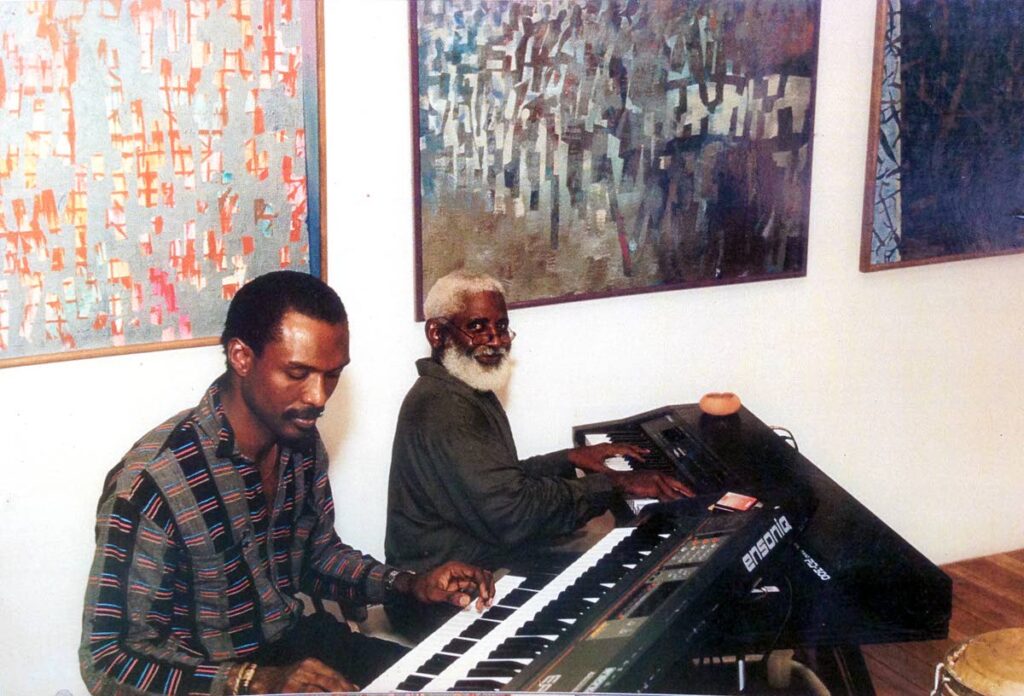

Zanda entered this environment with excitement and enthusiasm. He was part of the influx of returning professionals from the Windrush exodus to England. He was charismatic and was well received. His Afro-guru-like appearance was refreshing, as he brought his exuberant style and musical temperament into this already mixed cultural porridge.

In those days compositions were explored capturing the new style and themes: Andre Tanker’s Ah went Away, which later became Forward Home; Scofield’s Panyard Blues was the anthem; Kitchener’s Ole Lady the jam tune; Zanda’s Fancy Sailor was lingering, with this romantic air of something coming from deep within our local soul that was fresh and different…a beautiful calypso ballad.

There was also a back-in-times relation to Rupert Clemendor’s work also. There was a resurgence redoing folksongs like Mangoes, Any Time Ah Pass, and Shango hymns in different ways. Zanda kept these sonic doodlings in his later repertoire.

The young students at the time absorbed all and reproduced it in their modern way as new instrumentation and instruments such as electric pianos, Hammond organs and guitars were coming available. They also were composing, adding to the mixture…the porridge. This also added to the pre-soca treatment and development.

There was another level of exchanges seldom covered in this music bubble. It was the intellectual exchanges of professionals of the various liberal arts disciplines. The architects, poets, playwrights, UWI lecturers and even teachers from QRC – Scofield brought them all together. Zanda’s business partners architects Jack Bynoe and Clive Bacchus supported him.

There was Zanda’s take – “that architecture is frozen music” extended from his mentor, Trinidadian professor Oswald Glean Chase, who was an architect internationally known as a Bauhaus thinker, sociologist, photographer and painter.

Scofield’s saying was: “Jazz is not a noun. It is a verb. It is the becoming being actualised. It is the centre of improvisation.”

The ideas of form, constructivism, space, motif, the golden mean, the statement, compositional constructs, tension and release, of tone, rhythm, harmonic principles, modes and cosmologies of cross-cultural dynamics were topics and subjects discussed in this fraternal space.

Against the background of world events, in itself, there was a subliminal response to the new Ashe movements of Afro-Latin Caribbean, South America, the coming of reggae, soca, the zouk and the Tropicalist movement were arriving at the door of popular music in the region.

From Scofield’s institutionalising the concept of calypso jazz to Zanda’s rebranding kaiso jazz all under the umbrella of Caribbean jazz, Zanda’s promotion of pan and the jazz from on early qualifies him as father of pan jazz.

In the mid-80s National Petroleum produced a series called Pan Jazz – an international jazz festival with TT’s national instrument as the leading focus. Zanda was the one who initiated and was flagbearer of that creative cluster and inclusion.

The QRC Jazz Club filtered into Family Tree the Band and Clive Zanda’s Gayap. In 1970, Family Tree the Band had produced the concert Kaiso Caravan, the first series of Pan Jazz. The concert was the brainchild of Oliver Boothman, who was manager of Family Tree and Fitzroy Coleman. It was a collaboration with the early Phase II, Family Tree and Clive Zanda’s Gayap.

The concert featured ace guitarist Fitzroy Coleman, Len "Boogsie" Sharpe, Andre Tanker, Barry Howard, Boothman brothers Michael and David, Wayne Kirton, Clive Zanda, Andy Phillips, Angus Nunes, Rawle Mitchell, Michel Meggie Clarke, Earl Edwards, Mike Georges and others.

The concert represented the Caribbean jazz fraternity pioneered by the QRC Jazz Club, the "institution" where Pan Jazz really began and Caribbean jazz was explored.

Today, amidst misinformation and misrepresentation, little is known and researched of this austere institution and its significant contribution to the musical culture and aesthetic of TT and the Caribbean.

Clive Zanda was here. He has left to join our passed visionaries, musicians and transcendentalists who have left us something of ourselves that makes us Caribbean. His Fancy Sailor remains to remind us.

David Boothman is the founder of the Caribbean Renaissance Foundation and master artist in residence at the University of TT.